'The Film Fathers and the Pregnant Wife’

That’s my mum Winifred (L) pregnant with me, 1948 and Dad, Brian (L) and his dad JL. They are the cinema men exhibiting the American majors (MGM, Paramount, Twentieth Century Fox) and Cinesound & Movietone newsreels across Australian cities and country towns; before that JL exhibited the silents and was Manager of The Capitol Theatre, Melbourne from 1924-1938.

Mum is so vulnerable, her arms protectively crossed across her body, under the gaze of her father in law. These film fathers are part of me, as is our dear Mum, who struggled to find herself and a road to freedom. Memory Film is the story of an inner mind and outer culture (the personal and the political) ebbing and flowing towards freedom - falling apart, falling apart, always falling apart, yet pearls emerging from the mud.

Read more about Memory Film and where you can see it (streaming and on SBS TV & SBS On Demand later in 2025.

The Thornley picture business has had a huge impact on my life. JL (James) our granddad died in Melbourne c1956; that coincided with the arrival of television and the crash of the cinema business. We were in Tasmania and Dad (Brian Thornley) ran the Launceston Plaza and cinemas in Hobart. We moved to Melbourne in 1956 for Dad to take over the family cinema business with his brother. It was a turbulent time!

A man of great vision – bringing over the chariots from the set of the Ten Commandments – and an eye for practical improvements – he patented a device by which a ‘monitor’ in the cinema audience could adjust the volume as each reel was shown as sound varied quite erratically in the early ‘talkie’ years.

He wasn’t always open to changes, though. When the Tivoli Theatre decided (temporarily, due to the outrage that followed) to stop playing the National Anthem after each evening screening because it was usually a signal for the audience to rush to the doors, Mr Thornley refused to end the custom and said: “We don’t find much diving for the aisles…”

In 1936 Thornley went to Hollywood, where he met Bing Crosby, revealing to a magazine after his visit that Mr Crosby had a ‘remarkable knowledge’ of Australian horse-racing. On that same trip he met Cecil B De Mille, who was still making movies in the 1930s.

He retired from his role as manager of the Capitol in 1938".

Agnès Varda (1928-2019) was a Paris-based photographer and film director and a key figure in modern film history. She is much revered across the globe for her deconstruction of the documentary form and her boundary-pushing work. In a career spanning 57 years, Agnès Varda, is one of the most original and renowned of the French ‘New Wave’ directors; in fact she is the only female director associated with it – her early films anticipating the work of Godard and Truffaut.

In 'The Beaches of Agnes' we are in the mind of an Elder who is ‘essaying’: she weighs up her own life, pays tribute to her lovers, friends, family and colleagues. She time travels back into her own films – and into Demy's films. It is a tribute to cinema – to the nouvelle vaugue, to documentary, to fiction, to imagination, to creativity. There is a great freedom in this film – everything is possible – as in a Melies film. It is magic, the stuff of dreams.

In 'The Gleaners and I' Varda plays with representation – from Millet’s painting – which serves as visual metaphor and foundation text – and she transforms it into her own film text of gleaning. She pushes beyond the surfaces of Millet’s three gleaners and his framing – to blow open the edge of frame and ‘essay’ into her film’s themes; and she gives us herself and her gleaners in fleshy reality.

The people actually filmed in 'The Gleaners' – and the way she films with them – is worth thinking about. How does Varda achieve such a special quality in her interviews? – a feeling of compassion and intimacy – a sense of shared humanity. Varda says this: “The people I have filmed tell us a great deal about our society and ourselves. I myself learned a lot as I was making this film. It confirmed my idea that documentaries are a discipline that teach modesty”.

Last year (2021) I was writing about Varda's unique approach to film-making and I came across a thoughtful interview with her by Sheila Heti in The Believer (Issue 66). Sadly, this online magazine's link is no longer active, but here is a quote that expresses Varda's film-making ethic:

If it can be shared, it means there is a common denominator. I think, in emotion, we have that. So even though I’m different or my experiences are different, they cross some middle knot. It’s interesting work for me to tell my life, as a possibility for other people to relate it to themselves—not so much to learn about me… It’s a way of living, sharing things with people who work with me, and they seem to enjoy it.

Back in 1999, we were blessed to meet up with Agnes Varda at the Creteil International Women's Film Festival in Paris. A group of us Australian women filmmakers screened our films in a program called, Les Antipodes. What a wonderful experience! Varda, one of our great mentors! And yes, we need them.

|

| Margot Nash, Jeni Thornley with Agnes Varda, Creteil International Women's Film Festival, Paris 1999 |

Notes

Heti, S. (2009, October 1). An interview with Agnes Varda. The Believer. Issue 66. https://believermag.com/an-interview-with-agnes-varda/

Sheila Heti, Interviews. http://www.sheilaheti.com/interviews, accessed 9th August 2022.

An immersive film poem about transformation and ‘the personal is political’

|

| Digitising the Super8, Christina Sparrow, NFSA 2016 |

|

| Mizuko Kuyo, a Ritual for Unborn Children Japanese Buddhist ceremony for those who have had a miscarriage, stillbirth, or abortion |

For middle-class women like Jeni Thornley, who is interviewed in the film about her undoubtedly unpleasant experience, an unwanted pregnancy meant going to Sydney and having the abortion at a posh clinic in Macquarie Street once you’d paid £300—the mark of the procedure’s illegality being that you had to go at night instead of during the day. For working-class women, as Communist Party member Zelda D’Aprano outlines in horrifying detail in her autobiography, it meant scraping together a much smaller sum but with much greater difficulty, and surrendering yourself to the hands of a backyard butcher.

"it is difficult to imagine abandonment more frightful than that in which the menace of death is combined with that of crime and shame."

Fieldes’ rudimentary class paradigm is one of the reasons I left the Socialist Labour League in the early 1970s and became more deeply involved in women’s liberation, navigating the feminist maxim “the personal is political”. Subsequently, some years later, I found psychoanalysis, recovery programs and Buddhism to be necessary and vital companions, along with feminism, on the lifelong journey of liberation.

I want to pay tribute to African American writer and feminist bell hooks (1952-2021) at this point as she discusses feminism in such an insightful way – illustrating her desire to bring feminism to everybody. A recent obituary by Sarah Leonard (2021) bell hooks transformed feminism articulates this clearly:

“More than three decades earlier, in 1984, bell hooks (author and activist) had already sliced through those questions in her book Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center. Feminism’s aim is “not to benefit solely any specific group of women, any particular race or class of women. It does not privilege women over men. It has the power to transform in a meaningful way all our lives. Most importantly, feminism is neither a lifestyle nor a ready-made identity or role one can step into.”

By defining feminism so precisely in lucid and welcoming prose, hooks issued a challenge to all of us to participate in overturning what she frequently called the “imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy.” She also provided me with my own understanding of socialism by making clear that you can’t practice feminism while leaving the brutal hierarchies of capitalism intact. She referred in her writing not to the feminist movement but to “feminist movement.” As in, you get up and go....In short, the range of hooks’ work expressed a desire to bring feminism to everybody. It expressed her belief that feminism really could transform the whole world, and that each of us has a part to play” (Subtext, 17th December 2021).

Recently I read about this documentary“Mizuko”: Visual Exploration of the Grief & Search for Healing (dir: Kira Dane & Katelyn Rebelo); it explores the cultural, spiritual and personal implications of misuko – holding a memorial service for one’s unborn child. I have appreciated this water child memorial ritual for some years; it is such a healing ceremony that offers a way beyond the sad struggle of the pro/anti-abortion/pro-life debate that plagues our western societies.

|

| Mizuko kuyō water child memorial service Japanese Buddhist ceremony for those who have had a miscarriage, stillbirth, or abortion |

Postscript

For the record, Zelda D’Aprano was a sister in the free safe legal abortion struggle, and a colleague. We were privileged to document her equal pay activism in our feature film For Love or Money: the history of women and work in Australia (McMurchy, Nash, Oliver & Thornley, 1983). Distributor Ronin Films

In Press: Book chapter: ‘The enigma of film: memory film: a filmmaker’s diary‘, Constructions of The Real: Intersections of Practice and Theory in Documentary-Based Filmmaking, (eds.) K. Munro et al., Intellect Books Series: Artwork Scholarship: International Perspectives in Education, 2022.

|

| Grading the Super 8, Christina Sparrow, National Film & Sound Archive, Ngunnawal (Canberra) 2016. |

In Press: Book chapter: ‘“We are not dead”: Decolonizing the Frame’ – First Australians, The Tall Man, Coniston, First Contact and their predecessors.(ed.) E. Blackmore et al., The Routledge Handbook of Indigenous Film. 2022.

|

| Bullfrog and family, Coniston (2012) |

For Love or Money: A history of women and work in Australia is a feature documentary by Megan McMurchy, Margot Nash, Margot Oliver and Jeni Thornley released in 1983. This feminist classic was digitally restored from original film materials by the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia in 2017. The film has been in active distribution for over 40 years with Ronin Films and is available on VOD, DVD and DCP.

|

| Newcastle Barmaids, Tribune, 1962 |

The most synthetic of all art forms, film is the space in which the representative and symbolic birth of a female person can can take place through the reconstruction of her history. (Barbara Kosta, Recasting Autobiography, 1994: 164)

In a belated reading of Claire Johnston’s influential work as a 1970s cultural activist, Meaghan Morris attempts to clarify the paradox of feminism’s constructive approach to social change in the face of its skeptical approach to history. She argues that feminism’s difference from other radical political and aesthetic movements is characterised by modes of action “to bring about concrete social changes while at the same time contesting the very bases of modern thinking about what constitutes ‘change'” (“‘Too Soon, Too Late’: Reading Claire Johnston, 1970-81,” in Dissonance: Feminism and the Arts 1970-90, ed. C. Moore, 1994: 128). Morris’s essay is an attempt to think about what it takes for feminist forms of action (which include festivals and seminars, essays and films) to redefine (as well as survive) historical change.

Here, I draw on contemporary readings of Walter Benjamin’s disruptive concept of history to revisit the 1983 documentary film, For Love or Money (a collective film by Megan McMurchy, Margot Nash, Margot Oliver and Jeni Thornley). Assembling a vast amount of archival footage and adding a rhythmic and intimate voice-over, For Love or Money was part of a paradigm shift in feminist film-thinking, away from the concept of ‘the spectator’ towards cinema as a public sphere “through which social experience is articulated, interpreted, negotiated and contested in an intersubjective, potentially collective, and oppositional form.” (Miriam Hansen, “Early Cinema, Late Cinema” in Viewing Positions, ed, L. Williams, 1995: 140)

For Love or Money had its origins when Sandra Alexander, co-ordinator of the 1977 Women’s Film Production workshop, suggested to Thornley and McMurchy that it would be a good idea to get together all the images of women in Australian films and have a look at them. This dovetailed with a request, in 1978, from the organisers of the first Women and Labour Conference to the Sydney Women’s Film Group to make a film of all the archival images of women at work. These apparently modest requests resulted in six years of painstaking work of collecting, cataloguing, and reprinting film and photographic images.

|

| For Love Or Money Filmmakers, Sydney 1983 (photo Sandy Edwards) |

The formal challenge of narrating two centuries of Australian women’s history in a feature length film which used over two hundred film clips was further complicated by what Walter Benjamin identified as a crisis in the tradition of storytelling, evident since World War I when “men returned from the battlefield grown silent – not richer, but poorer in communicable experience.” (“The Storyteller” in Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn and ed. Hannah Arendt, 1970; reprint, 1992: 84). For Love or Money was conceived as an antidote to the exclusion of women from Australian national history, yet the problem of finding a suitable narrative form for communicating women’s historical experience was never fully resolved by the makers of For Love or Money:

"There were times when it got very frustrating because we would have liked to have structured For Love or Money differently. The showreel was great to cut; it was such fun because it wasn’t chronological and I could really play, in the editing, across periods. It didn’t have that dreadful rigid chronology. In trying to find another structure that was not chronological, there just came a time when we had to let go because no one came up with anything; no one solved it". (Margot Nash. Interview with the author, 1 July 1992).

The challenge facing the filmmakers, to find a non-chronological structure, can be understood in terms of the distinction between conscious, voluntary memory and the act of remembrance. Like Benjamin, Irving Wohlfarth contends that modern historiography is a “mere pile of souvenirs” which “substitutes voluntary memory for authentic remembrance”. (“On the Messianic Structure of Walter Benjamin’s Last Reflections,” Glyph 3, 1978: 166). This contention is particularly pertinent to the struggle to produce an authentic, feminist mode of remembrance in For Love or Money. Wohlfarth suggests one path to authentic remembrance via Benjamin’s claim that the epic is the oldest form of historiography, containing within it the story and the novel, and their corresponding forms of memory: the storyteller’s epic memory (gedachtnis) of short-lived reminiscences and multiple events; and the novelist’s perpetuating memory (eingedenken) dedicated to “the one hero, the one odyssey, the one struggle” (1978: 149-50). Distinguishing between the epic genre of the chronicle (associated with oral tradition) and the conflation of chronology with the idea of progress (in the novel), Wohlfarth poses a choice for the historian: “historicism’s universal panorama” or “highly particular interactions between past and present” (1978: 167).

For Love or Money adopts historicism’s “universal panorama” yet fractures it in three ways. Firstly, “multiple events” are narrated from a feminist perspective on the present, challenging standard accounts of Australian national identity built on mateship and the bush ethos. Secondly, the film evokes “particular interactions between past and present” through audio-visual montage-sequences and the voice-over, offering a history of “multiple reminiscences” rather than one of lone heroes. And thirdly, the film’s apocalyptic perspective, on the present (the atomic age) heralds the annihilation rather than the redemption of history.

A feminist, historical temporality is specified at the beginning and in the closing montage of For Love or Money. The opening montage of shots is accompanied by a non-Anglo woman’s voice-over which establishes that this will be a history from below: “We find heroes only in monuments in public parks, but I think the real heroes are us.” The closing montage includes photographs of the filmmakers at work on the film, followed by a compilation of scenes from local feminist films, and a voice-over:

"We go back. We ask what happened then. We find documents, diaries, letters, images. Stories are uncovered. The stories of women’s work.”

|

| Mother and children, Victorian Railways, 1951 |

Like Benjamin’s historical materialist, the filmmakers understand that historicism favours the victor, and that their task, as feminist activists, is to take the documents preserved by the victor and “brush history against the grain” (Benjamin, 248). This task is made all the harder by the disjuncture between photographic representation and the memory-image. As Kracauer reminds us, the recent past captured in the photographic image can become comic, like recent fashion (“Photography” in Critical Inquiry, 19.3, 1993: 430). A wry montage of marriage proposals from Australian feature films in For Love or Money exploits the comic effect of antiquated images of the recent past, inviting sceptical laughter at an outdated nationalism. This contrasts with the significance of the memory-image which “outlasts time because it is unforgettable” (Kracauer, 1993: 428).

At the time of its release in 1983, For Love or Money attracted vocal criticism for the way its first-person plural voice-over : “We remember her labour. We remember that she gave. What we were to each other”. “We” was heard, then, as producing a unified female subject of history and eliding differences between women. A retrospective viewing of For Love or Money offers another interpretation: that the collective “we” of female unity is fragmented into multiple reminiscences which work against the unifying voice of the narrator and against the linearity of historicist time. From this perspective, modernity’s conflicting temporalities (of race, class and gender) undercut the panoramic unity of the first-person voice-over in For Love or Money. Drawing on key events of national history (such as the long struggle for equal pay and women’s rotation in and out of the workplace at times of war) as the sites or loci of memory, the filmmakers organised a wealth of archival images into a new temporal order. This disruptive temporality serves to undercut the panoramic logic of a masculine, nation- building history. The “we” of the narration, then, brings together a multitude of voices.

For Love or Money begins with anthropological footage of Aboriginal women whose stories reverberate with the on-going consequences of their dispossession from the land. Their colonised modernity is a different temporality from that of white, settler women whose historical experience takes multiple forms under convictism, land settlement, industrial, and digital economies.

|

| Aboriginal Day of Mourning, Man magazine, Sydney 1938 |

The 1890s, the 1920s and the Depression of the 1930s constitute significant events in white women’s temporality. While working class women engage in struggles for equal pay, union representation and access to better paid ‘male’ jobs, middle-class women appear in the public sphere as reformers and campaigners.

The influx of a labour force of immigrants after World War II produces the greatest temporal shock since colonisation: southern European rural time is traded for the industrial time of the assembly line and its promise of mobility expressed in the anonymous voice-over, “Sometimes I dream I will be coming out of that bloody factory.”

In the 1920s and again in the 1950s, as the commodification of housework and child care intensifies, women enter new temporalities as consumers of modern, privatised lifestyles. In the 1960s access to higher education propels the postwar generation of upwardly mobile young women (including the filmmakers) into an oppositional public sphere defined by the New Left and the liberation movements.

How, then, is a feminist narration of history to end if not in the present as a redemptive awakening through women’s liberation? In the interests of a united women’s movement, For Love or Money, at one level, attempts to subsume the film’s multiple reminiscences into one temporality. It stages the present as “a state of emergency” (Benjamin, Theses 248), a disruptive “now-time” that appears in modernity’s ultimate eruptive image: Hiroshima. The narrator declares: “We are the daughters of the atomic age: numb, silent, grieving.” While this is a point of unity in the film, multiple endings pile up as different histories are brought to a standstill by the image of the atomic mushroom cloud.

The first of the film’s endings begins with footage of a women’s demonstration, accompanied by a voice-over which seeks “new meanings for work,” challenging “work ruled by profit, efficiency, progress, war.” The film acknowledges its own historicist impasse when its careful documentation of the ninety-year struggle for equal pay ends with the statement, “Progress, but it didn’t really change things.”

The second ending begins with a slow motion shot of women in black, arms linked, faces quietly determined, as they participate in the first Anzac Day commemoration of women raped in war. The voice-over declares, “We are women of the nuclear age. We resist. We place our bodies in the way.”

|

| The Sydney Women Against Rape in War Collective, Anzac Day, George St Sydney 1983 |

The image track cuts abruptly to a third ending with a shot of Aboriginal artefacts hanging on a wall, followed by an aged photograph of Aboriginal women. A new voice speaks over the Aboriginal song:

“Listen to us. Our country is very beautiful. It is our grandfathers’ country and our grandmothers’ country from a long time ago. It is the sacred soil of the dreamtime. Why do you never understand?”

A fourth ending begins with stills of the filmmakers, seeking to construct a new, feminist temporality, as they work with images and stories they have uncovered. This ending contrasts the daughter’s story of resistance with the mother’s “story of the kitchen, the story of the clean house.” A compilation of mother-daughter photographs, accompanied by a ‘hymn to the mother’ is followed by shots of men holding their children:

“We ask what might happen if men learnt the story of women’s work.”

At this point the film seems to be over, but the return of the problem of women’s work and the maternal is displaced by a last-minute reprise of the activist ethos in the resonant image of the Anzac Day memorial march for women: an image that fades, blurs, turns to blue and finally to black. What is the future of this deeply mournful image – an image of feminists born under the sign of Hiroshima, mourning unknown women raped in war?

For Love or Money ends in a nuclear present where the cessation of history (and its modernist myth of continual progress) threatens to be apocalyptic rather than redemptive. Osborne is critical of the persistence of apocalyptic narrative in Benjamin’s thinking, especially the emphasis on a “generalized sense of crisis, characteristic of the time-consciousness of modernity as perpetual transition” (Osborne, The Politics of Time, 1995: 157). Osborne revives the discourse of political modernism when he argues for now-time “as an integral moment within a new, non-traditional, future-oriented and internally disrupted form of narrativity” which cannot be co-opted into reactionary refiguration “of history as a whole” (158-9).

For Love or Money occupies a space between historicist and materialist forms of narrative: it draws on multiple temporalities to refigure “history as a whole” in order to bring it within the grasp of the present moment. Yet, the attempt to grasp history in the present (to arrive at a future-oriented ending) is precisely the point at which narratives of crisis, redemption, or apocalypse fall into ruin. This breakdown of historical narrative, in the present, marks the moment of skepticism in feminism’s experimental practice of history.

Screening the Past publishes material of interest to historians of film and media, to film and media scholars, to social historians interested in the place of film and media within general history, to film makers interested in the history of their craft or in representing history through their productions, to film and media librarians and archivists.

I would like to show my respect and acknowledge the Traditional Custodians of the Land, the Darkinjung, their Elders past and present on which this special Avoca Cinema IWD event is taking place.

Lyndall Ryan asked if I could say a few words about the making of the film, its purpose as a feminist film and how it stands today... and I hope Lyndall will also say a few words to on how the film fares today!

So firstly I would like to acknowledge my collaborators, Megan McMurchy, Margot Nash, Margot Oliver and Lyndall (who was the historical consultant on our Penguin tie-in book); also Lyndall’s mother Edna Ryan – feminist activist and labour historian who is interviewed in the film, and whose analysis contributes much to the film’s economic analysis of women’s position.

Really, the purpose of the film was to create a visual, moving story about Australian women’s campaigns for wage justice and gender equality – campaigns for a just society, a civil society.

And we also wanted to make a film that interrogated and subverted the representation of women in Australian cinema. In the 70s there were few female film directors. The depiction of women tended to place women in passive, subservient roles. The daily experiences of ‘real women’ in the work place or at home were ignored.

Making the film

Ours was a spirited and long collaborative six year process - beginning with the 1978 Women and Labour Conference; the groundbreaking work of feminist historians was tumbling out in print form: books, articles – but there was no film that documented Australian women and work with any historical perspective or economic analysis, or that documented women’s radical activism to achieve, the vote, equal pay, property rights, legal abortion and child care.

We began our work in the archives - National Film and Sound Archive. Megan and I saw almost every Australian documentary and feature film produced - and we analysed every film from the perspective of how it represented women - selecting sequences to create the film. Meanwhile Margot Oliver joined us, and with a socialist feminist labour history perspective, starting recording interviews with women across Australia. The impulse was to seek out activist women, like Zelda D’Aprano, Edna Ryan and many others, like the great Aboriginal activist Pearl Gibbs.

Margot Nash joined us as the film's editor and Elizabeth Drake came on board as composer. We recorded over 35 interviews (film and audio), printed footage from our selected archival film and photographic collections, did extensive manuscript research and wrote many versions of the script and narration! Through all this was raising the budget to make the film. See the end credits and you will get a sense of scale.

How is the film relevant to today?

Well, first, let’s consider local IWD’s 2013 demands:

• stop violence against women

• end breastfeeding discrimination

• affordable childcare

• ratify the migrant workers' convention

And from one spectrum to the other: In the board room only 5% of CEO’s are women. And in many Aboriginal communities the position of women is totally vulnerable due to both endemic historical racism – white privilege creating exclusionary work place practices; add to that the complexities of domestic violence, poverty – these are basic human rights issues needing urgent attention.

For Love or Money, provides a broad historical and economic analysis, still relevant today – especially our analysis of ‘the double day’ and women’s unpaid work in the home – which we named "the work of loving" in the film.

In my view For Love or Money could have a new chapter, Chapter 5, to bring it up to the present. Perhaps as an online collaborative documentary that is open for all women to contribute to - for all of us to tell stories that are relevant today – and to network with each other around our concerns. I see our For Love or Money facebook page as a stepping stone to this kind of interactive website; we can all make it relevant to now!

For Love or Money is streaming online at Ronin films ; and DVD's can also be purchased via Ronin; also copies of the For Love or Money Penguin tie-in book are at Ronin.

|

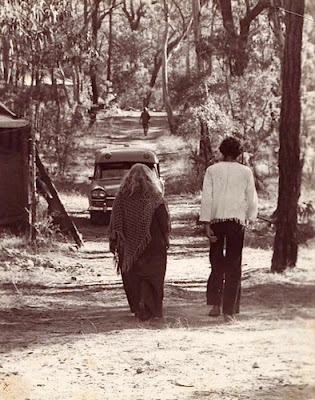

| Nell Campbell, Robyn Moase, Theresa Jack, Lisa Peers, Journey Among Women |

"Journey Among Women is the black sheep of the family. Insanely uninhibited, the convict survival story is too steeped in graphic nudity and violence to sit alongside critic's darlings like My Brilliant Career (1979), Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) or The Getting of Wisdom (1978). But it is also too artistically and intellectually noteworthy to be embraced by the genre B-movie aficionados."

|

| Camera assistant, Jeni Thornley, Journey Among Women, Super8 screen shot |

|

| Jude Kuring, Di Fuller, Journey Among Women |

|

| Nell Campbell, Lisa Peers, Journey Among Women |

|

| L-R Nell Campbell, Robyn Moase, Tom Cowan, Rose Lilley, Peter Gailey, Jeni Thornley, Journey Among Women |

|

| Uni of SA 2018 |

A Betraying Camera?

"Betrayal is the theme that keeps rising to the surface in this extraordinary film. Did the director, producer and cinematographer betray the women cast and crew members? Were the women divided amongst themselves, as was rumoured, with the lesbian and radical separatist and the non-separatist women each feeling themselves betrayed by the other group or by women who crossed from one group to another? If you look closely you can see all these questions as well as the answers. By placing betrayal at the centre of concern, Journey Among Women reveals the diversity of ideas and opinions among the cast and crew. What is fascinating is that these fissures can all be seen inside the film's frames."

|

| Jeune Pritchard, Journey Among Women |

Outside the film's frames – "the charge of the real"

|

| Christina Sparrow, NFSA Film Services, 2016 grading the Journey Among Women Super8 |

|

| Sydney Women Against Rape Collective, Anzac Day March, Sydney 1983 |

"She'd seen women fight, she'd seen them unite, she'd seen them show courage and resourcefulness. Give them a clear issue and they cut right through to the bone of it and stood solid as a rock."

|

| Anzac Day "We Mourn all Women Raped in all Wars", Sydney 1983 Super8 screen shot |

"Let's also honour Dorothy Hewett who wrote the screenplay with Tom Cowan and John Weiley. Watching the film, I could sense Dorothy's mind at work and the women actors intense contributions; I really valued the film more than I ever have – rather more as a documentary archive, if you like, than a drama."

"I was living in the bush, in Berowra Waters, and it was so powerful. I happened to read this French science-fiction story called Les Guérillères (Monique Wittig 1969) about a future society of women - like an Amazon society - who were at war with the rest of society. Somehow in the combination of the wildness and strangeness and beauty of the bush and this story of wild women, I saw a parallel in how we perceived the bush and how the British first saw the bush as ugly. Well, we now see it as beautiful. And how the sort of excesses of radical feminism, when it began, were seen as ugly - ranting and raving and being abusive and so on. But, in fact, behind it were very beautiful things - not just the women, but the humanist ideas."

|

| Dorothy Hewett and Tom Cowan on location Journey Among Women |

|

Jeune Pritchard, Norma Moriceau, Journey Among Women

Super8 screen shot

|

Michele Johnson 1952-2019 Actor

|

| Michele Journey Among Women Super8 screen shot |

References

Simon Foster (2009), Journey Among Women Review, A brutal, lost Australian classic, SBS Reviews, 7th December.

Jane Mills, (2009), 'Journey Among Women - Special and Electric': booklet accompanying Collectors Edition DVD, Journey Among Women, Umbrella Entertainment.

Claire Johnston (1973), Notes on Women's Cinema, London, Society for Education in Film and Television.

Benjamin Law and Beverley Wang (2019), 'Going beyond the hashtag with Me Too founder Tarana Burke', Stop Everything, ABC Radio National, 15th November 2015.

|

| Still from The Silences |

Here are the edited notes to my talk:

"Firstly I am going to contextualise The Silences in its genre or mode and then talk a little about the film itself. The Silences takes it place in the rich and diverse genre of the essay film, the autobiographical film and the personal film. As well, we can place it in the dynamic tradition of women’s and feminist filmmaking which erupted during the 1970s women’s liberation movement – which Margot and I were both so strongly involved.

|

| Margot Nash, Jeni Thornley with Agnes Varda Creteil Women's Film Festival, Paris 1999 |

|

| Still from Tu as Crie |

The Silences enters this corpus of innovative films and shares, too, many of their textual strategies–piercing into the heart of repression – the filmmaker peeling back layers one by one – to gaze directly into the mirror of self, family and society. Frequently, in these films, there is a personal, subjective narration – the “I” voice. And often they are inter-textual, drawing on film and photographic sources from the filmmaker’s personal archive and film work.

Agnes Varda’s Beaches of Agnes and Sophia Turkiewicz’s Once my Mother are distinctive inter-textual films, as is The Silences. In The Silences Margot draws on her own family photographs and skilfully weaves scenes from her previous films, such as Vacant Possession, and takes, if you like, a second look at these texts, in the context of her family and its secrets.

We, the viewers, might now experience the original text on a deeper layer, looking back along with the filmmaker’s probing, self reflexive, gaze. This inter-textuality reveals, as Margot writes (quote) “the psychological context in which the earlier films were produced, allowing the viewer to understand the relationship of creativity to experience”.

I also suggest that this intertextuality – because it involves juxtaposing excerpts from fictional films into the documentary mode – produces what documentary theorist Stella Bruzzi refers to (quoting Vivian Sobchack) as “the charge of the real”. Now we read fiction as documentary evidence of family trauma – such fleshy bodies – viewer, filmmaker and persons filmed – all joined together; this affect is striking in its intensity.

|

| Sophia Turkiewicz (R) and her mother (L) |

|

| Still Our Hitler |

In The Silences we sense this aesthetics at work too; certain key images in family photographs are examined and re-examined for clues – the clues reverberating into the excerpts from Margot’s archive of constructed dramatic films.

|

| Still The Silences |

|

| Still Beaches of Agnes |

Documentary film theorist, Bill Nichols, in dialogue with the home movie essayist Peter Forgács said, "I experience your films as a gift, an unexpected act of generosity or love..." And I feel that too about The Silences. We are really privileged tonight to join with Margot on this journey and to watch the film with her here! Thankyou."

|

| Still The Silences |

Dr. Jeni Thornley

11 March 2019

|

| Our Pa, (Tom William Butcher) and his postcard sent to our Nan in Tasmania (Wynne Ila Lette), from France 10th Dec.,1917 |

Jim Everett, pura-lia meenamatta

'Near the end of his latest book, Forgotten War Henry Reynolds makes a demand: the Australian War Memorial must commemorate the frontier wars. The book examines Australia’s violent colonial history, and reaches into some of our most challenging public debates – about land rights, sovereignty, and reconciliation...I also spoke to playwright Jim Everett, a Plangerrmairreenner man, of the Ben Lomond people in northern Tasmania. ‘If they asked me, I’d say “no we don’t want to be stuck alongside you mob – we had to fight you”. If we want to remember our heroes, then we should be doing it ourselves,’ he says. ‘We should be dedicating a part of country to our fallen heroes – perhaps we could mark it with a rock. I don’t like the idea of statues.’

|

| Jim Everett (arrested) while protecting the kutalayna site, April 2011 |

raped in all wars"

|

| Canberra 1981 (?) (re the red circled person in the pic- I have no idea who it is!). |

|

| Anne Tenney as The Mother in To The Other Shore; pic Sandy Edwards |

|

Port Arthur Historic Convict Site, Tasmania, Super8 screen shot

|

This is a still of me and screen mother Jovana Janson from Film for Discussion a film Sydney Women's Flm Group made in the early 1970s. I play a young woman in a crisis about work, life and identity- triggered by her encounter with feminism. The film was nominated for Best Documentary, Greater Union Awards, Sydney Film Festival 1974. SWFG was one of the first Australian groups to establish itself in the name of 'Women’s Liberation'. Film For Discussion is a docu-drama shot in 1970 and completed until 1973. The film sought to encapsulate in an experimental form issues that were under discussion within the Women’s Liberation Movement and so contribute to action for change. The link is to Ballad Films the website of Martha Ansara, my friend and colleague. Martha was a key person in my becoming a filmmaker, alongside my Dad who was a film exhibitor. It was Martha who introduced me to the actual possibility of women making their own films. It doesn't seem that radical in 2017, but in 1969 it was! Go on this site and order a copy of the film and also see other films to purchase by Ansara. Film For Discussion screened this year (2017) in Feminism and Film: Sydney Women Filmmakers, 1970s-1980s at Sydney International Film Festival.

|

| Sydney Film Festival Retrospective June 2017 Feminism and Film Sydney Women Filmmakers, 1970s-1980s L-R filmmakers Jeni Thornley, Megan McMurchy, Susan Charlton (curator), Margot Nash, Martha Ansara

'From archive into the future'

A great review in this latest issue of RealTime by Lauren Carroll Harris. She writes about 'For Love or Money' (McMurchy, Nash, Oliver & Thornley 1983) and the recent Sydney Film Festival's Retrospective Feminism & Film: Sydney Women Filmmakers, 1970s & 1980s

"For Love or Money stands today as a major work of historical research, a masterclass of montage editing and a classic essay film".

|

|

| still from For Love or Money: Barmaids Strike, Newcastle c 1962 (Tribune Archives, thanks Martha Ansara) |

We all see and experience this early history from our own perspective and involvement- so the dates and details will naturally differ. I remember being part of the SWFG formation, The Sydney Filmmaker's Co-op, Women Vision, The Women's Film Workshop 74; the lobby for 50% female intake into AFTRS in IWYear 1975, the International Women's Film Festival 1975, the Women's Film Fund (I became Manager in 1984-85); and later the Women's Film Units, FFW formation 1978; Film Action formation, and all the inter-related women's groups (like Women and Labour etc) and the many political organisations all connected.

Summary

- Feminist Film Workers formed in 1978 (as a splinter group of the Sydney Women’s Film Group). The membership of this seven member group was: L-R Beth McRae, Carole Kostanich, Sarah Gibson, Jeni Thornley, Martha Ansara, Margot Oliver, Susan Lambert

- With a Women's Film Fund Grant, FFW set up at the Women's Warehouse, Ultimo (Sarah Gibson became the full time distribution worker). The Women and Work Film's (later FLOM's ) first office was in WWH (me, Margot Oliver and Megan). Later we moved to edit the film with our editor Margot Nash at 'Lorraine', Redfern.

|

| For Love or Money team: L-R Margot Nash, Megan McMurchy, Jeni Thornley, Margot Oliver. photo: Sandy Edwards 1983 |

Also Don't Shoot Darling : Womens Independent Filmmaking in Australia (ed Blonski 1987) has several articles on women and film groups (by Jenni Stott and Jeni Thornley) incl photographs connected to the FFW (by Sandy Edwards).

"In 1979 the Minto Discussion Weekend was held where women filmmakers and theorists came together to debate film, politics and theory. It was an initiative of the Feminist Film Workers who formed in 1978 as a splinter group of the Sydney Women’s Film Group to focus specifically on education, distribution and exhibition of feminist films."

"In 1979 the Catalogue of Independent Women's Films was published by the SWFG (ed B.Allysen). Early in 1979, a full-time position in distribution at the Coop was secured for a women's filmworker, after the FFW were able to show that the rental of women's films accounted for 50% of the total rental income at the Co-op. In the same year, the FFW secured a grant of $20,000 from the Women's Film Fund to operate an office away from the Co-op and pay a full-time worker who would who would engage in the promotion of the feminist films in its collection, to increase print sales...The Co-op continued to handle the rental of FFW's films, however" (Stott in Blonski (ed) 1987: 120).

With the Women's Film Fund Grant, and with Sarah Gibson as full time distribution worker, some of the events and activities of FFW included:

- The Film/Theory practice weekend, Minto, Nov 1978 (Martha Ansara wrote a Film News essay

- "Women propose a New Feminist Cinema", Season Sydney Film-Co-op, Dec 1978

- "The Image of Women in Australian Feature Films" Forum, Sydney Film Festival June 1979 (Carolyn Strachan presenter).

- Publication of FFW Discussion Papers No.1, 1979) (Thornley in Blonski (ed) 1987: 89-92).

This poetic 52min cine-essay, about race and Australia's colonised history and how it impacts into the present, is screening online Monday 25 July 10am - Tuesday 26 July 10am (AEST) anytime in that 24hours, and then weekly until December on the Culture Unplugged Film Festival site here:

'Remembrance, in the wake of suicide'

If you haven't read any Deborah Bird Rose (anthropologist, eco-philosopher in environmental humanities) – her recent blog: "Remembrance, in the wake of suicide" is a confronting beginning: she offers her very thoughtful reflections on the disturbances in the ongoing colonising nation called Australia: "Gerry Georgatos, a specialist on Indigenous suicide, describes the problem as a ‘humanitarian crisis’. Also read Bird Rose's ground breaking 2004 book: "Reports from a Wild Country: Ethics for Decolonisation"'Discovery, settlement or invasion?'

'It was the best of times, it was the worst of times'.

The other day I read of a new light show art installation by British artist Bruce Munro at Uluru: "Field of Light": the tourist mecca – canapés and champagne while gazing at the wonders of the Red Centre at sunset...meanwhile Rosalie Kunoth-Monks (OAM, 2015 NT person of the year and Arrernte-Alyawarra Elder) says that Aboriginal people living in remote outstation Utopia are starving:

"Utopia represents sixteen remote outstations 260 kms north east of Alice Springs. Rosalie lives in one of the outstations with her daughter Ngarla and grandchildren. Rosalie and Ngarla have reported that the elderly in the communities have not been receiving their regular daily meals as expected through the current aged care program. When meals have arrived they have not been nutritious".

Militarism, Projection and Anzac Day - a few reflections.

Dear Reader, I wrote this blog for Anzac Day in 2014. I re-post it as it is as relevant today as then. To work towards peace is for me the path. I honour our Grandpa who fought in France; he was no lover of war- and his letters home to our beloved Nana are testament of that. So, rather than a photo of him in war uniform I post this photo of him diving from the bridge at the Gorge, Launceston (he is 3rd from our left).

|

| Our Pa, (Tom William Butcher) and his postcard sent to our Nan in Tasmania (Wynne Ila Lette), from France 10th Dec.,1917 |

Jim Everett, pura-lia meenamatta

'Near the end of his latest book, Forgotten War Henry Reynolds makes a demand: the Australian War Memorial must commemorate the frontier wars. The book examines Australia’s violent colonial history, and reaches into some of our most challenging public debates – about land rights, sovereignty, and reconciliation...I also spoke to playwright Jim Everett, a Plangerrmairreenner man, of the Ben Lomond people in northern Tasmania. ‘If they asked me, I’d say “no we don’t want to be stuck alongside you mob – we had to fight you”. If we want to remember our heroes, then we should be doing it ourselves,’ he says. ‘We should be dedicating a part of country to our fallen heroes – perhaps we could mark it with a rock. I don’t like the idea of statues.’

|

| Jim Everett (arrested) while protecting the kutalayna site, April 2011 |

raped in all wars"

|

| Canberra 1981 (?) (re the red circled person in the pic- I have no idea who it is!). |

A few years ago I was at a Conference and Michael Renov gave a paper where he spoke about his notion of the 'four fundamental tendencies of documentary' :

A few years ago I was at a Conference and Michael Renov gave a paper where he spoke about his notion of the 'four fundamental tendencies of documentary' : My talk, 'the archive of the self and deconstructing the national archive' – was part of "Maestros of the Archive: The Art of Archival Documentary", Ozdox Forum, August, 2014: "Gathering, manipulating and presenting archival material is an art form, one that is sometimes overlooked. Through archival film making, a seasoned story teller can tap into our nostalgic tendencies, our memories and collective subconscious with precision and eloquence". In this Ozdox Forum I presented along with Paul Clarke, Shane McNeil and Nicole O’Donohue. Curator was Brendan Palmer, with moderator Ruth Hessey.

The focus of my talk is: what image do you choose to represent or communicate an idea, or a feeling; how do you work with your own subjective memory…and how might your own personal archive link to public history - the historical record of a nation; and where does your intention and ethics play out in all of this?

%2Bin%2Btherapy%2B9.12.tiff) |

| Anne Tenney in To The Other Shore 1996 (pic: Sandy Edwards) |

|

| Our Pa, (Tom William Butcher) and his postcard sent to our Nan in Tasmania (Wynne Ila Lette), from France 10th Dec.,1917 |

Jim Everett, pura-lia meenamatta

'Near the end of his latest book, Forgotten War Henry Reynolds makes a demand: the Australian War Memorial must commemorate the frontier wars. The book examines Australia’s violent colonial history, and reaches into some of our most challenging public debates – about land rights, sovereignty, and reconciliation...I also spoke to playwright Jim Everett, a Plangerrmairreenner man, of the Ben Lomond people in northern Tasmania. ‘If they asked me, I’d say “no we don’t want to be stuck alongside you mob – we had to fight you”. If we want to remember our heroes, then we should be doing it ourselves,’ he says. ‘We should be dedicating a part of country to our fallen heroes – perhaps we could mark it with a rock. I don’t like the idea of statues.’

|

| Jim Everett (arrested) while protecting the kutalayna site, April 2011 |

raped in all wars"

|

| Canberra 1981 (?) (re the red circled person in the pic- I have no idea who it is!). |

|

| Mirdidingkingathi Juwarnda Sally Gabori's Dibirdibi Country (2008) |

The sentient power of country and the spirits who reside within it is not to be underestimated. Still today, trespassing on another's country is a reckless and dangerous act. It is customary in many parts of Australia to be formally "introduced" to country by traditional custodians, which can take the form of an exchange of sweat or a baptismal dousing so the land will accept or sense one as a countryman or woman and not make the newcomer sick. Almost invariably, senior community members will walk ahead at a special site, calling to their ancestral spirits so they will recognise and not harm the visitors.

It is in this context that the "welcome to country" has evolved; and it is a culturally appropriate means of brokering a social engagement with another community by formally recognising their ties to their homelands in the contemporary world.

It is a matter of no small concern that there has been the inevitable invasion of anti-political correctness creeping into this profoundly symbolic gesture of respect, particularly in areas where the Western legal criteria used to determine native title rights dispossess the traditional custodians from any other form of public recognition. The criticism of federal Opposition Leader Tony Abbott that the protocol is merely a "genuflection to political correctness" could be applied equally to singing the national anthem. How many Australians know all the words of the anthem, and how many really believe that we are a nation "young and free"?

The welcome is an appropriate way of reiterating the message that Australia is home to the oldest continuous cultural tradition in the world, as a counterpoint to the endless parade of men on horses immortalised in bronze that line our city streets.

|

Our Pa |

ya pulingina milaythina mana mapalitu

mumirimina laykara milaythina mulaka tara

raytji mulaka mumirimina

mumirimina mapali krakapaka laykara

krakapaka milaythina nika ta

waranta takara milaythina nara takara

waranta putiya nayri

nara laymi krakapaka waranta tu manta waranta tunapri nara.

Greetings to all of you here on our land

It was here that the Mumirimina people hunted kangaroo all over their lands

It was that the white men hunted the Mumirimina

Many Mumirimina died as they ran

Died here on their lands

We walk where they once walked

And their absence saddens us

But they will never be dead for us as long as we remember them.

This is the eulogy of the Risdon Cove Massacre of 1804 where Tasmanian Aborigines were killed in an encounter with British soldiers. Greg Lehman says, "Regardless of the debate over how many were killed, it certainly constitutes Tasmania’s first massacre. But was it simply a regrettable over-reaction to the accidental appearance of a hunting party? Or was it something much more tragic?" His (2006) article is entitled, Two Thousand Generations of Place-making.

This film Putuparri is in process and raising money via crowd source funding site Pozible.

Support this film now; you can make a donation and receive a DVD of the finished film.

But hurry....52 hours only left on pozible!

"Ten years in the making, Putuparri is a compelling feature length documentary about an extraordinary 42 year old Wangakjunga man living in Fitzroy Crossing. Located in the remote Kimberley region of north western Australia, Putuparri Tom Lawford lives a two way life - traditional and contemporary".

The energy of cultural exchange and shared consciousness is a significant quality that visual ethnography offers the documentary tradition. It is also a mode of filmmaking with a strong foundation in Vietnam and in its tertiary education. Vietnamese visual ethnographers are making films from perspectives within their own culture, not as observers representing ‘the other’ —perhaps as a consequence of having achieved liberation from French and American colonisation. Also, it is not surprising that many of the films are working through complex issues around tradition and modernity given the largely agrarian population and its multi-ethnicity—with over 50 distinct groups, each with its own language and cultural heritage. I appreciated many of the films and the engaged discussions that took place around them.

Filmmaker Tu Thi Thu Hang participated in many of the discussions and she often shared deeply about Vietnamese history and events that had affected her family in the immediate post war period. Tu Thi Thu Hang structures her recent film, The Old Man Who Sells Bananas (2012), so that the audience starts out with ‘her’ mis-perception of the Old Man.

I think that the ethical in itself. . . has a sort of functioning dimension, and it is also glued to this notion of a common desire or impulse: an ethical impulse, that one can see as an underlying and consistent theme that cross the history of documentary. How do I. . . what is my relationship with this other? What do I mean to that person, what does that person mean to me, what’s at stake in representing others?So I think Renov's finely tuned insight that 'the ethical' is fundamental to documentary is so relevant - not only to today- but to the whole history of documentary. The 'ethical' is the frame by which we both make and study documentary.

+to+Know,+killing+drawing+copy.jpg)